Business data backup and recovery

Data backup and recovery are pillars of business cybersecurity. It protects organisations from catastrophic incidents such as accidental data deletion, data corruption, malware attacks, and natural disasters.

However, poorly designed or badly maintained backup systems can fail, leaving organisations with a false sense of security.

This guide explains how business backup and recovery work, covering backup techniques, storage locations, security considerations, and operational best practices.

Contents:

- Why data backup and recovery are critical for businesses

- How business data backup and recovery works

- Types of data backups for businesses

- Business backup data security

What is business data backup?

Business data backup is the systematic process of creating and retaining independent, recoverable copies of an organisation’s systems, applications, and data so they can be reliably restored following an incident.

A true backup and recovery solution includes:

- Defined retention periods (days, weeks, months, years, or decades)

- Independent storage (on-site, off-site, or cloud-based)

- Verifiable restore capability (regularly tested recovery)

- Independent administrative and identity controls, separate from production systems

In practice, this is delivered through dedicated backup platforms and services such as enterprise backup platforms (e.g., Veeam, Rubrik, or Datto), combined with off-site repositories, immutable storage, and long-term archival systems.

Business backups are medium to long-term in nature and are designed to support resilience, risk management, and disaster recovery rather than day-to-day convenience. They are intentionally isolated from production environments to protect against corruption, deletion, or compromise.

Business-grade backups do not include application auto-saves, file version history, or sync tools used by platforms such as Google Docs, Microsoft Word, or WordPress, as these mechanisms support productivity and availability but do not provide independent recovery copies.

Backed-up data may include operating systems, application data, configurations, databases, files, records, security logs, intellectual property, and regulated or historical data retained for many years.

Backup strategies are flexible and risk-based. Critical systems may be protected using continuous or high-frequency backups, while less sensitive datasets are often captured daily, weekly, or monthly, depending on business impact and recovery requirements.

Backups protect organisations against incidents such as hardware failure, human error, cyberattacks (including ransomware), software faults, and physical events like fire or flooding.

Backup data may be stored on-premises, off-site, in private cloud environments, or on public cloud platforms, depending on the priority: fast recovery, geographic resilience, or long-term secure retention.

Why data backup and recovery are critical for businesses

Data backup and recovery act as an insurance policy against data loss. The more important the data, the greater the impact of losing it, whether the loss results from a server room flood, a ransomware attack, or simple human error.

Consequences include:

- Prolonged operational downtime: When critical systems or data become unavailable, normal operations can stop, such as when a server failure prevents staff from accessing customer records or core applications. Effective backups enable fast restoration and reduced disruption.

- Direct financial loss: Data loss can lead to immediate costs, such as lost sales during an outage or emergency IT recovery expenses. Reliable backups limit these losses by allowing systems to be restored quickly rather than rebuilt from scratch.

- Regulatory non-compliance: Many regulations require organisations to retain and recover data, such as the UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018, for personal data. Inadequate backups can leave organisations unable to restore records after an incident, resulting in regulatory breaches and potential penalties.

- Reputational damage: Service disruption or data loss can damage trust. For example, when customers are unable to access online services for extended periods. Rapid recovery through backups helps minimise customer impact and protect brand confidence.

How business data backup and recovery works

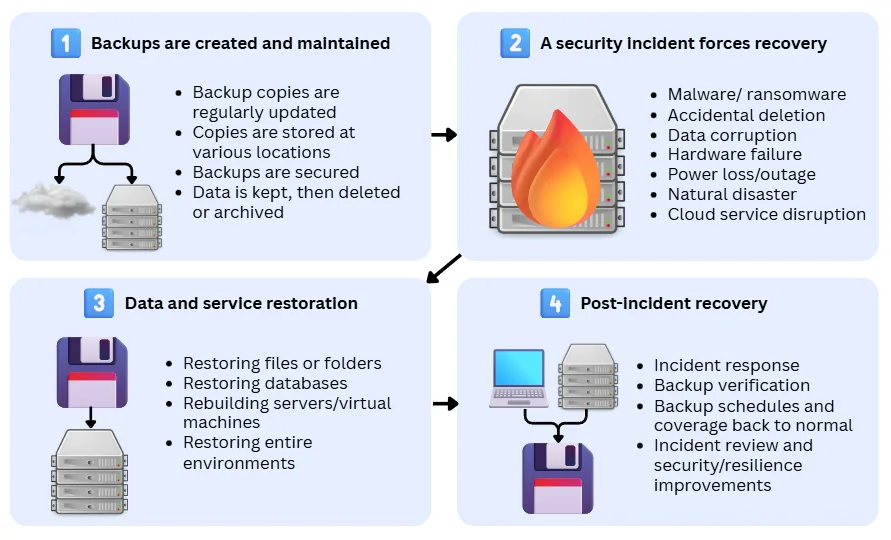

Backup and recovery is an operational loop in which data is continuously protected. When an incident occurs, backups are used to restore services and data to an agreed state.

This process varies greatly in complexity and scope depending on the system, but the process typically follows the same four steps:

1. Backups are created and maintained

Business backup systems are highly automated and produce backup copies on a schedule or trigger, and are managed over time. The backup process typically involves:

- Regularly creating backup copies (full, incremental or continuous changes are saved as copies)

- Storing copies in one or more locations (often including an off-site or isolated copy)

- Protecting backups (access controls, encryption, immutability where required)

- Managing lifecycle (retention rules: keep, delete, or archive backups as they age)

- Monitoring success/failure and reporting backup status

Read on below on how to implement business data backup.

2. A security incident forces a recovery response

Backups run in the background until production data is no longer usable. This forces security teams to trigger data recovery from the backups. In critical systems, a recovery response may be automated to minimise downtime.

Common triggers include:

- Malware or ransomware

- Accidental deletion or overwrites

- Data corruption or failed updates

- Hardware failure, power loss, or outage

- Natural disaster or physical site loss

- Cloud or third-party service disruption

3. Data and services are restored from backups

Backups are used to return systems to a known-good state.

This may involve:

- Restoring individual files or folders

- Restoring databases to a specific point in time

- Rebuilding servers/virtual machines and restoring data onto them

- Restoring entire environments (for larger outages)

Restoration can be automated (predefined workflows) or manual (operator-led), depending on the organisation and the severity of the incident.

4. Recovery is completed and normal protection resumes

Once services are restored, work continues to stabilise operations and prevent repeat incidents.

This typically includes:

- Incident response actions (containment, eradication, root cause analysis)

- Verification that restored data is correct, and systems are stable

- Re-establishing normal backup schedules and coverage

- Creating fresh backups after recovery (to capture the recovered “known-good” state)

- Reviewing what happened and improving controls (processes, monitoring, security, recovery procedures).

Data backup and recovery guiding principles

Backup and recovery systems vary widely between organisations. Each solution combines different backup techniques, storage locations, security controls, and management models to suit the systems it protects.

Despite this, most backup strategies are designed around four guiding principles, which help balance resilience, cost, complexity, and risk, and provide a common framework for decision-making:

The 3-2-1 backup rule

The 3-2-1 rule is a foundational principle for reducing the risk of total data loss. It prevents a single failure, whether technical, human, or malicious, from destroying all recoverable copies of data.

It states that organisations should maintain:

- 3 copies of data (one primary production copy, two backup copies)

- 2 different types of storage or media (e.g. disk and cloud, or on-site and off-site systems)

- 1 copy stored off-site or isolated (e.g. in a secondary air-gapped location or in the cloud)

The rule is scalable and applies to both simple, non-critical systems, as well as complex, sensitive data.

Recovery Time Objective (RTO)

Recovery Time Objective (RTO) defines how quickly a system must be restored after an incident. In other words, organisations need to determine how long a system can be unavailable before the impact becomes unacceptable.

RTO is typically measured in time units such as minutes or hours, and varies significantly between systems.

For example, critical operational systems may require very short RTOs (seconds/minutes), while supporting or non-critical systems may tolerate longer outages (hours/days).

Shorter RTOs generally require higher investment in infrastructure, automation, and operational readiness.

RTO directly influences:

- Backup technique (frequency and depth) and storage location

- Whether fast local restores are required

- The need for automation, replication, or standby environments

Recovery Point Objective (RPO)

Recovery Point Objective (RPO) defines how much data loss is acceptable, measured as a period of time.

For example, an RPO of 24 hours means up to one day of data loss is acceptable, while an RPO of 15 minutes means data must be protected almost continuously.

Lower RPOs require more frequent backups and more sophisticated backup mechanisms.

RPO determines:

- How frequently backups must run

- Whether incremental, differential, or continuous backup techniques are required

- Storage and bandwidth requirements

Retention period objectives

Retention objectives define how long backup data must be preserved and remain recoverable. They determine the historical depth of recovery and are driven by business, regulatory, and risk-management requirements.

Retention periods are typically measured in days, months, or years, and often vary by data type or system. For example, operational system backups may be retained for weeks or months, while financial records, security logs, or regulated data may require retention for several years or longer.

Retention objectives directly influence:

- Storage capacity and cost

- Backup storage tiering (hot, warm, cold, archive)

- The use of immutability and retention locks

- Compliance with legal and regulatory obligations

- Protection against delayed or undetected incidents

Types of data backups for businesses

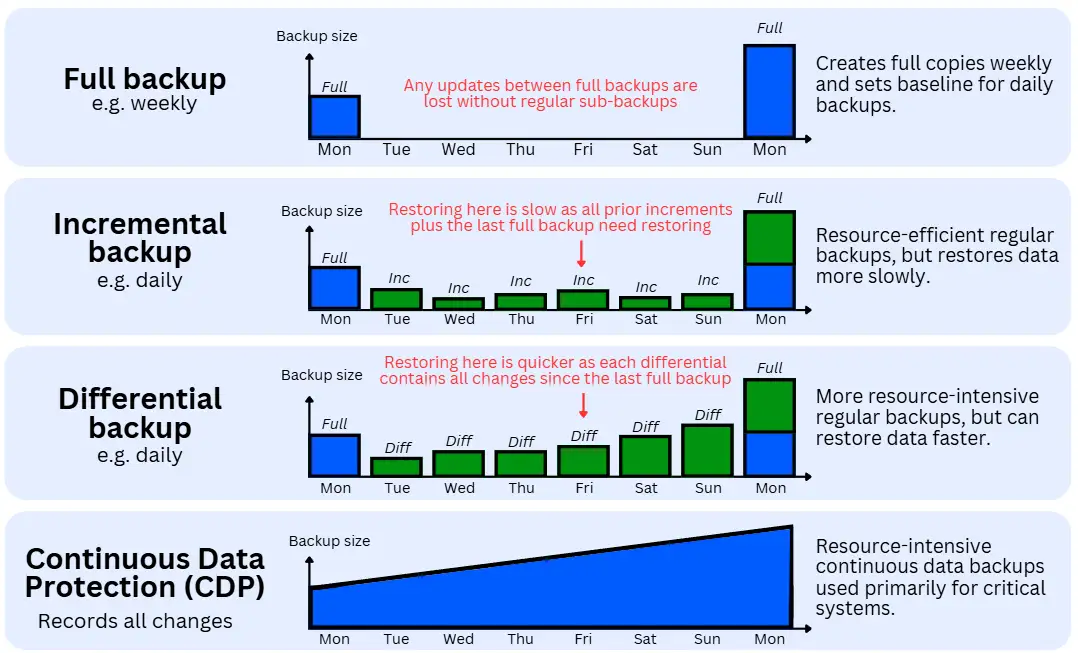

Businesses use different backup techniques to meet varying recovery and retention requirements across systems and data.

Backup is not as simple as creating full copies of every system, as bandwidth, storage, and computational resources are always limited.

To address this, four primary backup techniques are commonly used to support a range of business needs:

Full backup method

Key purpose: Makes a master copy of the targeted data for disaster recovery.

A full backup is the most familiar method, in which a complete copy of all selected data is taken at a specific point in time.

It is the master copy that is relied on in disaster recovery scenarios, such as when systems are destroyed by fire or hardware failure, or when environments must be fully rebuilt following a serious malware or ransomware incident.

Taking a full copy requires the largest compute, bandwidth and storage, so it is typically done as infrequently as possible.

Except for small systems (GBs of data), full backups are rarely used as regular backups. The master copies generated by full backups may be stored in the cloud, data centres, or servers, depending on the use case.

Incremental backup method

Key purpose: Keeps full backups up-to-date with minimal overhead until the next full backup.

An incremental backup captures only the data that has changed since the last backup. It does not duplicate data but records deltas (new or modified files, records, or data blocks) since the previous backup.

This minimalist approach is designed to consume the least possible compute, bandwidth, and storage resources, making it well suited to high-frequency, always-on environments (e.g., cloud platforms and SaaS applications) where data changes continuously.

The trade-off is slower restore speed. Reconstructing a previous state takes longer, as the backup software must replay and reassemble each incremental change in the backup chain before producing a restored copy.

Historically, incremental backups were considered less reliable than differential backups due to a higher risk of chain corruption, but modern backup systems mitigate this through integrity checks, redundancy, and advanced indexing, making incremental backups the default method for regular backup operations.

Differential backup method

Key purpose: Keeps full backups up to date with an emphasis on faster recovery.

A differential backup captures and accumulates all changes made since the last full backup. Unlike incremental backups, it does not reset after each run; instead, each differential backup grows larger over time until a new full backup is performed.

Its primary advantage over incremental backups is restore speed. All changes required to recover a given dataset are contained in the most recent differential backup, reducing the number of steps needed during restoration. The trade-off is increased resource consumption, as storage, compute, and bandwidth requirements grow with each successive run.

Although its use has declined over the past decade due to significant improvements in incremental backup technologies, differential backups remain a cornerstone in certain niche environments where predictable and rapid recovery is prioritised.

Continuous data protection (CDP)

Key purpose: Near-real-time protection for systems where data loss is unacceptable.

Continuous Data Protection records changes to data continuously, or at very short intervals, rather than relying on scheduled backup windows.

This creates a fine-grained change history that enables recovery to almost any point in time within the retention period (typically hours or, at most, days).

CDP significantly reduces the risk of data loss but requires more complex infrastructure and careful operational management. As a result, it is typically reserved for the most critical systems rather than deployed across an entire environment.

Because CDP retains all intermediate data states leading up to the current live state, storage requirements can grow rapidly. For this reason, CDP is generally suitable only for short-term protection and is often complemented by traditional full and incremental backups for longer-term retention.

Other backup methods for businesses

The term “backup” is often used inaccurately to describe technologies that do not create independent, historical recovery copies, which is the defining purpose of a true backup.

The following methods are commonly confused with backup techniques but serve different objectives, typically data availability, replication, or convenience.

Snapshot-based backups

Snapshots create point-in-time views of a system to support short-term rollback, usually by referencing an underlying storage state. Snapshots do not store independent copies of data; they record metadata that maps a prior state.

They can be created almost instantly and consume minimal additional storage. However, if the underlying storage is corrupted, deleted, or compromised (e.g. by ransomware), snapshots are often lost or encrypted as well.

Snapshots enable rapid recovery from recent or accidental changes (similar to Ctrl + Z), but they do not constitute a reliable or independent recovery copy.

Mirroring/data replication

Mirroring (or replication) maintains a live copy of data for high availability. Data is continuously copied from a primary system to a secondary system, often in near real time, providing redundancy and improving uptime.

However, replication is not a backup method because it does not preserve historical states and cannot support point-in-time recovery. Any corruption, deletion, or malicious change is faithfully replicated to the secondary system.

Sync-based file backups

File synchronisation tools (such as cloud sync services) keep files consistent across devices or locations, ensuring the most recent version exists in multiple places. While convenient for collaboration (e.g. Google Docs), they prioritise consistency rather than recoverability.

Changes, overwrites, and deletions are synchronised across all locations, often permanently. Version history, where available, is typically limited and insufficient for disaster recovery.

Where do businesses and backup providers store backup data?

The location where backup data is stored directly affects backup and restore speed, security, resilience, and cost. Businesses typically use a mix of on-site, off-site, and cloud-based storage options.

On-site backups

On-site backups are stored on hardware located within the organisation’s premises, such as servers, NAS devices, or local data centres.

They are commonly used to protect local file servers, applications, and databases that require fast recovery, particularly in environments with large data volumes, limited internet bandwidth, or strict performance requirements.

On-site backups often form the first recovery layer in a broader multi-location 3-2-1 backup strategy.

Pros

- Very fast backup and restore speeds, especially for large datasets and short recovery windows

- Ideal for supporting local systems and applications

- Cost-effective when on-site infrastructure already exists

- Greater control over hardware, access, and security

Cons

- Vulnerable to physical disasters (fire, flood, theft)

- Susceptible to ransomware if not properly isolated

- Requires off-site or secondary copies to be considered resilient

Off-site backups

Off-site backups are stored in a separate physical location owned or managed by the organisation, such as a secondary office or data centre.

These locations are typically connected via high-performance wide area network (using dark fibre, MPLS, or Business Ethernet links, often supported by SD-WAN solutions).

They are commonly used to enable rapid recovery if a primary site becomes unavailable, particularly in organisations with multiple locations or formal disaster recovery requirements.

Pros

- Protection against primary site failure

- Faster restore times than public cloud in many cases

- Full control over infrastructure and data locality

Cons

- High infrastructure and operational cost

- Requires dedicated networking

- Still vulnerable to regional disasters or wide area network failure

Public cloud backups

Public cloud backups are stored on third-party cloud platforms such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform (GCP).

They are widely used as an off-site backup destination due to their scalability and geographic redundancy, and are especially common in small to mid-sized organisations and cloud-native environments.

They work best under high-performance, fully dedicated leased line business broadband services.

Pros

- Virtually unlimited storage capacity

- Built-in geographic redundancy

- Reduced hardware and maintenance overhead

- Easy to scale as data grows

Cons

- Restore speeds depend on internet bandwidth

- Costs can be high with frequent restores or large data volumes

- Less direct control over underlying infrastructure.

Private cloud backups

Private cloud backups are stored in virtualised environments fully controlled by the organisation or a dedicated provider, or hosted by specialised private cloud providers in dedicated data centres.

This approach is often adopted where regulatory, compliance, or data sovereignty requirements demand tighter control than public cloud platforms provide.

Pros

- Greater control over security and compliance than public cloud

- Predictable performance due to dedicated infrastructure

- Flexible, managed architecture similar to a public cloud

Cons

- Higher cost than public cloud

- Requires skilled management and monitoring

- Less “elastic” at smaller scales than public cloud (i.e. does not scale easily)

Offline/air-gapped backups

Offline or air-gapped backups are stored on systems or media that are physically or logically disconnected from production environments, such as LTO tape libraries, logically isolated backup repositories, or offline archival storage facilities.

They are commonly used as a last line of defence against ransomware and systemic compromise, particularly for critical or long-term data.

Pros

- Strong protection against ransomware and systemic compromise

- Data cannot be altered remotely

- Commonly required for cyber resilience or insurance compliance

Cons

- Very slow restore times

- Manual handling and operational complexity

- Not suitable for frequent recovery scenarios

Business backup data security

As part of an organisation’s digital estate, backup and recovery systems need the same protections as live systems and business networks, and sometimes stronger.

There have been past cases of successful cyberattacks on backup and recovery systems which greatly compounded their impacts.

The following security domains are critical to ensuring backup systems remain secure and trustworthy.

Access control and identity management

Only authorised users and systems should be able to access backup data or perform backup and restore operations. Strong access control limits insider risk and reduces the impact of compromised accounts. Key controls typically include:

- Role-based access control (RBAC) separates backup operators, administrators, and auditors

- Least-privilege access (users only get the minimum permissions required)

- Multi-factor authentication (MFA) for administrative access

- Separation of duties between backup management and production system administration

- Dedicated backup service accounts rather than shared credentials

Encryption and data protection

Backup data must be protected both while stored and during transfer. Encryption ensures that even if backup data is accessed unlawfully, it cannot be read or misused. Common requirements include:

- Encryption at rest for all backup data

- Encryption in transit between systems and backup storage

- Secure key management (keys stored separately from backup data)

- Regular key rotation and access restrictions

- Support for customer-managed encryption keys where required

Immutability and ransomware protection

Backups must be protected from alteration, deletion, or encryption by malware. These controls ensure backups remain trustworthy during ransomware or systemic compromise events.

Typical controls include:

- Immutable backups (write-once, read-many for a defined period)

- Time-based retention locks that prevent early deletion

- Logical or physical isolation of backup storage

- Air-gapped or offline backup copies for critical data

- Protection against administrative deletion or override

Monitoring, logging, and alerting

Backup systems must be continuously monitored to detect failures, misuse, or suspicious activity. Monitoring allows issues to be detected early, before backups are needed for recovery. This usually includes:

- Logging of all backup and restore operations

- Audit logs for access attempts and configuration changes

- Alerts for failed backups, unusual deletion attempts, or permission changes

- Integration with central logging or security monitoring systems (SIEM)

- Integration of backups as endpoints for Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR)

- Retention of logs for forensic and compliance purposes

Segmentation and isolation

Backup infrastructure should be isolated from production systems. Common approaches include:

- Network segmentation (e.g., VLANs in local area networks)

- Dedicated backup management networks

- Restricted inbound and outbound connectivity (using gateways or firewalls such as WAFs and NGFWs)

- Separate authentication domains or trust boundaries

- Avoiding shared credentials between production and backup systems

- Isolation prevents attackers from moving laterally from compromised systems into backups.

Data integrity and verification

Backup data must be accurate, complete, and usable when restored. Integrity controls ensure backups can actually be relied upon during recovery. Typical controls include:

- Integrity checks (checksums, hashes, or verification scans)

- Automated validation after backup creation

- Regular restore testing to confirm usability

- Detection of silent corruption or incomplete backups

- Versioning to protect against gradual data corruption

Compliance, privacy, and data protection obligations

Backup data is subject to the same legal and regulatory requirements as production data. Compliance requirements often influence where backups are stored and how long they are retained. Common considerations include:

- GDPR and personal data protection requirements

- Data residency and geographic storage restrictions

- Retention and deletion rules aligned with industry-specific cybersecurity compliance

- Right-to-erasure handling in backups where applicable

- Auditability and documentation for regulatory reviews

Operational security, governance, and RACI ownership

Clear processes and accountability must support backup security. Governance ensures backup security remains effective as systems and threats evolve.

A RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) model should be defined for backup and recovery activities to ensure ownership is explicit and understood. This is particularly important during incidents, when ambiguity over responsibility can delay or prevent recovery.

At a minimum, responsibility should be clearly assigned for:

- Configuring and maintaining backup systems

- Monitoring backup success and failure

- Managing access, encryption, and immutability controls

- Performing and validating restore tests

- Authorising and executing data restoration during incidents

- Organising preventive cybersecurity awareness training for staff involved in backup and recovery operations

How to implement business data backup and recovery

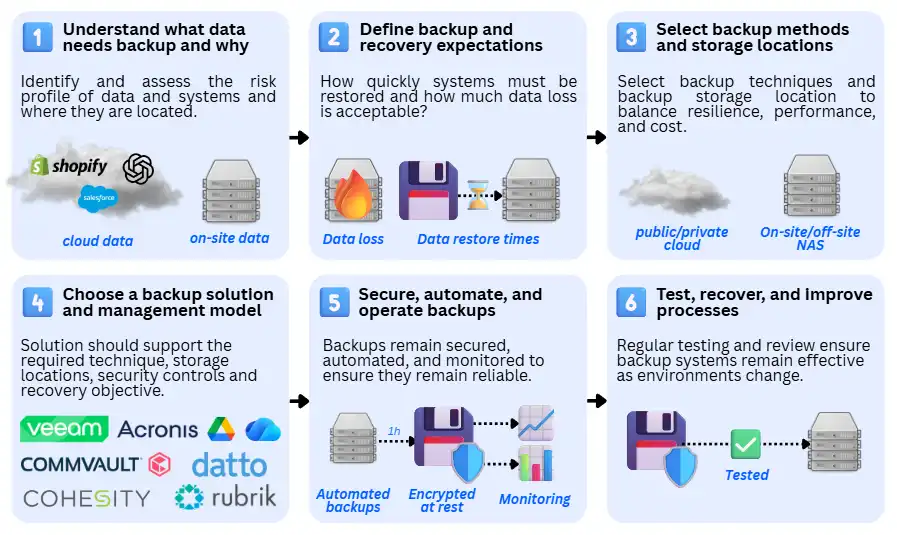

Implementing business data backup is not a single technical task but a structured process that scales with system complexity, data criticality, and organisational risk. While tooling and infrastructure differ, most organisations follow the same core phases:

1. Understand what data needs backup and why

The first step is to identify and assess the risk profiles of data and systems, and to determine where they are located. This establishes the scope of backup and prevents over- or under-protection.

Here are examples of what this would look like for various systems:

Simple systems (e.g., microbusinesses) typically store data in devices, email, and shared cloud storage (e.g., Google Drive), including documents, invoices, and customer records. Data ownership is informal, and most data is treated as equally important.

Commercial systems (e.g. SMEs, local councils): Include multiple shared systems such as file servers, email platforms, CRMs, and line-of-business databases. Data is grouped by business function and importance, with clear ownership.

Enterprise systems (e.g. enterprises, public institutions): Cover large and diverse estates including applications, databases, virtual machines, SaaS platforms, logs, and configurations. Data classification and dependency mapping are formal and documented.

2. Define backup and recovery expectations

Once the data landscape is understood, organisations define how quickly systems must be restored and how much data loss is acceptable. These expectations guide all later technical decisions.

Simple systems (e.g. microbusinesses): Recovery expectations are usually informal, with tolerance for hours or days of downtime and limited historical retention.

Commercial systems (e.g., SMEs, local councils): Retention time (RTO) and recovery points (RPO) targets are defined for critical systems based on business impact, with retention aligned with operational and regulatory needs.

Enterprise systems (e.g. enterprises, public institutions): Recovery targets are formally approved, tiered by system criticality, and often linked to legal, regulatory, and contractual obligations.

3. Select backup methods and storage locations

With recovery expectations defined, organisations choose appropriate backup techniques and where backup data will be stored, balancing resilience, performance, and cost.

Simple systems (e.g. microbusinesses): Use basic full or incremental backups stored in cloud platforms or a single off-site location. 3-2-1 is always recommended, but commonly ignored at this scale.

Commercial systems (e.g. SMEs, local councils): Combine full and incremental or differential backups, stored across on-site systems and off-site or cloud locations following the 3-2-1 principle.

Enterprise systems (e.g. enterprises, public institutions): Use layered approaches including incremental backups, continuous data protection for critical workloads, immutable storage, and geographically separated or air-gapped copies. 3-2-1 remains the baseline, but is often surpassed (e.g. 5-3-1).

4. Choose a backup solution and management model

Once backup methods and storage locations are defined, organisations select a backup solution and management approach that can reliably deliver those requirements at the appropriate scale.

The chosen solution should support the required backup techniques, storage locations, security controls, and recovery objectives, without introducing unnecessary operational complexity.

Simple systems (e.g. microbusinesses): Typically rely on all-in-one or built-in backup capabilities that require minimal configuration and ongoing management. These solutions are self-managed and prioritise ease of use over granular control. Examples include Google Drive or Microsoft OneDrive plus a local NAS.

Commercial systems (e.g. SMEs, local councils): Commonly use centralised backup platforms that protect multiple systems from a single interface. These solutions balance automation, visibility, and security while remaining manageable by small IT teams. Examples include Veeam, Acronis, and Datto, plus an on-site server.

Enterprise systems (e.g. enterprises, public institutions): Use enterprise-grade backup and recovery platforms designed for scale, policy-driven control, and regulatory compliance. These solutions integrate with security, audit, and incident response processes and support complex hybrid environments. Examples include Commvault, Rubrik and Cohesity.

5. Secure, automate, and operate backups

Backup systems must be secured, automated, and monitored to ensure they remain reliable and protected from compromise.

Simple systems (e.g. microbusinesses): Rely on built-in security, basic encryption, and simple notifications.

Commercial systems (e.g. SMEs, local councils): Use role-based access, MFA, encryption, monitoring, and documented procedures.

Enterprise systems (e.g. enterprises, public institutions): Implement strict access controls, isolation, immutability, continuous monitoring, and integration with security and compliance tooling.

6. Test, recover, and improve backup and recovery

Backups only provide value if they can be restored reliably. Regular testing and review ensure backup systems remain effective as environments change.

Simple systems (e.g. microbusinesses): Occasional manual restores to confirm data is accessible.

Commercial systems (e.g. SMEs, local councils): Scheduled restore tests for critical systems, with issues tracked and resolved.

Enterprise systems (e.g. enterprises, public institutions): Formal disaster recovery exercises, audit reviews, and continuous improvement driven by testing outcomes and incident learnings.

Issues with data backup and recovery and how to handle them

As a core cybersecurity solution, backup and recovery systems often encounter issues. Some are avoidable through good design and operational discipline, while others are inherent trade-offs between cost, complexity, and risk.

The following are the most common issues, particularly in smaller and simpler environments.

Backups exist but cannot be restored: They may be incomplete, corrupted, or missing dependencies because restore testing was never performed. This is addressed through regular restore testing and integrity validation.

Backups are compromised during ransomware incidents: Backup systems are often accessible from production environments, allowing attackers to delete or encrypt them; this is mitigated through isolation, immutability, and separate access controls.

Not all data is being backed up: New systems, cloud services, or data sources are frequently overlooked as environments evolve; this is handled by maintaining an up-to-date backup inventory and monitoring coverage.

Recovery takes too long during incidents: Backup storage or recovery workflows are not aligned with business recovery objectives. This is resolved by defining RTOs and using faster, more local recovery paths for critical systems.

Backup storage costs grow unexpectedly: Data growth and retention are unmanaged, leading to excessive storage consumption; this is controlled through tiered retention, archiving, and regular capacity reviews.

Human error undermines backup reliability: Manual processes are misconfigured, skipped, or forgotten over time; this is reduced through automation, documentation, and clear ownership.

Compliance and privacy risks are overlooked: Backups contain regulated or personal data but are not governed to the same standard as production systems; this is addressed by applying encryption, retention controls, and audit logging to backup data.

Are backups included in Microsoft 365 or Google Workspace?

Microsoft 365 and Google Workspace are commercial productivity and collaboration platforms that include built-in data protection, availability, and short-term retention capabilities.

These features provide a degree of resilience against everyday user errors and service disruptions but are not designed or positioned as complete backup solutions.

From a technical and governance perspective, these features do not constitute a true backup because data retained within Microsoft 365 or Google Workspace remains:

- Within the same service boundary

- Governed by the same identity systems, administrative controls, and retention policies as production data

As a result, they do not provide fully independent, long-term recovery copies.

That said, many microbusinesses and very small organisations rely on these native capabilities as their primary form of data protection.

For low-risk environments with limited compliance obligations, this approach is often considered “good enough,” particularly where data volumes are small, recovery requirements are informal, and there is an additional offline or off-site copy as part of a 3-2-1 backup strategy.

However, neither Microsoft 365 nor Google Workspace guarantees protection against scenarios such as:

- Misconfigured or modified retention policies that result in permanent data loss

- Malicious or accidental bulk deletion by privileged users

- Account compromise where changes propagate across the platform

- Long-term recovery requirements beyond defined retention windows

- Audit-grade, point-in-time restores over extended periods

Business backup and recovery FAQs

Our business cybersecurity experts answer common questions about backup and recovery, particularly for small and mid-sized organisations.

What data should a business back up first?

It’s best to start with data and systems that would immediately stop operations if lost, such as core business applications, customer records, financial data, and identity systems. Less critical data can be backed up less frequently or retained for shorter periods.

How long does it take to restore business data from a backup?

Restore times vary widely and depend on data size, storage location, and system complexity. Restoring small files may take minutes, while restoring large systems or full environments can take hours or longer. This is why Recovery Time Objectives (RTOs) should be defined in advance.

What happens if a backup fails without us knowing?

If backup failures go undetected, data may be unrecoverable during an incident. This is why monitoring, alerting, and regular restore testing are critical parts of any backup strategy, not optional extras.

Can backups be used as evidence for compliance or audits?

Yes, provided they are properly secured, retained, and auditable. Backup data is often required to demonstrate regulatory compliance, data retention, and recovery capability, but only if access controls, logging, and retention policies are correctly implemented.

Who should be responsible for data backups in a business?

Responsibility should be clearly assigned to a role or team, not left implicit. While IT or security teams usually manage backups, accountability for backup policy and recovery readiness should sit with management.