Identity security for businesses

Identity security is a branch of cybersecurity that manages human and non-human access to systems to prevent unauthorised use.

It encompasses everything from the cryptographic technologies that prevent identity fraud to practical controls such as password managers, multi-factor authentication (MFA), and identity monitoring.

This article explores the multi-layered technology stack behind identity security, why it matters for businesses, and how to implement an effective approach regardless of organisation or industry.

Contents:

- Why identity security matters for businesses

- The main components of identity security

- How identity security supports zero trust

- Building an effective identity security strategy

What is identity security?

Identity security is the branch of cybersecurity that focuses on managing the authentication, protection, and permissions of both human and non-human users, and controlling how they access systems.

At a high level, identity security ensures that:

- Only authorised humans or applications can access systems

- Authenticated users are granted only the minimum level of access required

- Access can be revoked, accounts disabled, or credentials rotated following a security incident

This applies to all identities accessing a system, including employees, contractors, partners, service accounts, applications, and APIs.

Identity security manages these groups across an organisation through a combination of:

- Technologies (e.g. passkeys, biometrics, multi-factor authentication)

- Processes (e.g. Joiner–Mover–Leaver user lifecycle management)

- Policies (e.g. conditional access, role-based access control)

In larger organisations, identity security is often managed by a dedicated team within cybersecurity, working alongside network security and monitoring functions.

Its importance has grown as organisations adopt cloud platforms, APIs, and remote or hybrid working models. Traditional perimeter-based defences are no longer sufficient when users and systems access resources from multiple locations and devices.

Modern security increasingly centres on protecting identities wherever they operate, across cloud environments, web applications, third-party integrations, and APIs, making identity security a foundational component of today’s cybersecurity strategy.

Why identity security matters for businesses

Identity breaches have become the primary way attackers gain access to systems. Below are the key reasons why protecting identity is critical:

- Protect against the most common attack vector: Most breaches now begin with compromised credentials obtained through phishing, password reuse, or leaked API keys rather than direct network attacks.

- Protect against lateral movement: Without strong access controls, a single compromised account can provide access to email, cloud applications, data stores, and administrative tools.

- Reduces the risk of ransomware and data breaches: Robust identity controls limit what attackers can access or encrypt, even if they successfully authenticate.

- Secures remote and hybrid working: Identity security enables users to work safely from any location without relying on outdated, perimeter-based defences.

- Supports regulatory and cybersecurity compliance requirements: Many security and data protection frameworks require controlled access, least privilege, and auditable identity management.

- Create a scalable security foundation: Implementing strong identity security early allows organisations to securely onboard new employees, contractors, partners, third-party applications, and integrations as they grow.

The main components of identity security

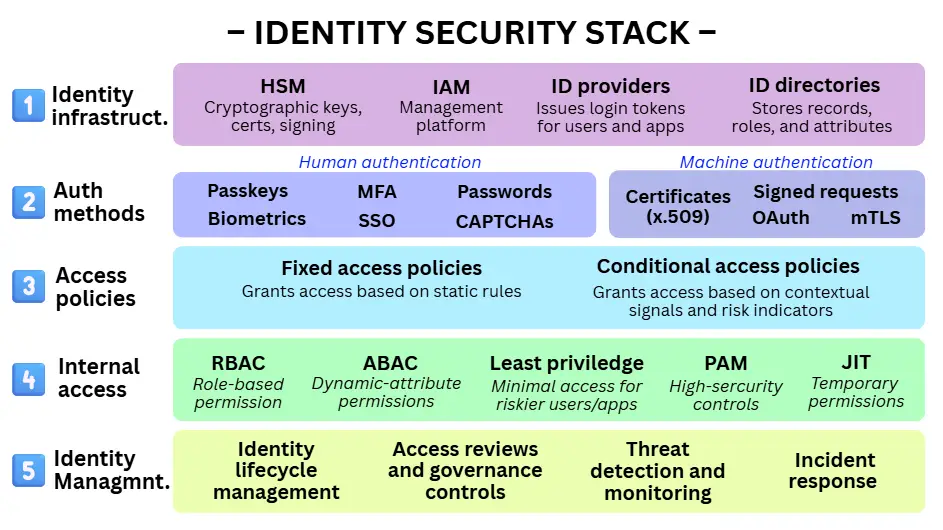

Identity security is a multi-layered stack of technologies, controls and policies that work together to prevent unauthorised access to systems and data.

This layered stack is hierarchical. At its foundation, cryptography ensures that identities stored within identity platforms cannot be forged or tampered with. The stack then builds upwards through authentication, access control, and privileged access, culminating in long-term monitoring and governance.

Each layer depends on the one below it, and weaknesses at any level can undermine the effectiveness of the entire identity security strategy.

Below are the core components, from foundation to operation.

1. Core infrastructure for identity security

The foundation of identity security begins by defining where identity data resides and which systems are trusted to assert identity. This base layer underpins all authentication and access decisions across the organisation and includes:

Cryptographic trust and hardware security modules (HSM)

Role: Protect cryptographic material underpinning identity systems

Cryptographic keys, certificates, and signing operations form the backbone of trust in identity systems. HSMs provide secure, tamper-resistant storage and management of sensitive cryptographic material used by IAM platforms and identity providers.

Identity and access management (IAM) platforms

Role: Central platform that coordinates identity security

IAM platforms act as the control plane for identity security. They unify identity providers, directories, authentication methods, and access policies into a single system that consistently manages identities at scale. Examples include Microsoft Entra ID and Google Cloud IAM.

Centralised identity providers

Role: Authenticate identities and issue trusted assertions

Identity providers authenticate users and applications and issue tokens or assertions that grant access to connected systems. They are often integrated into IAM platforms operated by vendors such as Microsoft, Google, Amazon, or Okta.

Identity directories and attribute stores

Role: Store trusted identity records and attributes

Directories store identity records, group memberships, roles, and attributes. This information informs authentication flows, access decisions, and authorisation models across the stack.

2. Authentication methods to prove identity

With the foundation in place, this layer focuses on verifying the identities of humans and machines. These controls prove that an identity is genuine, similar to presenting a passport or driving licence in the physical world.

Usernames and passwords

Role: Baseline authentication for human users

Passwords remain common but are inherently weak when used alone. They should be reinforced with additional controls to reduce risk.

Passkeys and biometrics

Role: Stronger, modern methods of human authentication

Passkeys and biometric factors reduce reliance on shared secrets and improve resistance to phishing. They are typically used as part of multi-factor authentication.

Multi-factor authentication (MFA)

Role: Strengthen authentication through multiple verification factors

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) requires users to present more than one verification factor, such as something they know and something they have. It significantly reduces the risk of account compromise. A common example includes a password combined with a one-time code from an authentication app.

Single sign-on (SSO)

Role: Centralised human authentication across multiple platforms.

SSO allows users to authenticate once and access multiple systems, improving usability while maintaining consistent security through the IAM.

Password managers

Role: Improve password strength and hygiene

Password managers help users generate and store strong, unique passwords, particularly where SSO is not available across all platforms.

CAPTCHAs

Role: Distinguish legitimate human interaction from automated abuse

CAPTCHA reduces automated attacks by verifying that a request originates from a human rather than a script or bot. It is not an authentication method, as it does not verify identity or credentials, but an access abuse mitigation control commonly deployed alongside authentication mechanisms.

Machine, workload, and API authentication

Role: Secure authentication for non-human identities

Applications, services, and APIs authenticate using cryptographic mechanisms such as:

- Certificates (x.509): Prove the identity of an application or service through trusted cryptographic chains.

- OAuth 2.0/OIDC tokens: Signed tokens issued by an identity provider to authenticate applications and request scoped access

- Mutual TLS (mTLS): Both client and server authenticate each other using certificates

- Managed identities (cloud-native): Cloud-provided service identities that remove the need for embedded credentials

- Signed requests: Cryptographic signatures validating the integrity and origin of API calls

3. Access policies: Static or contextual

This layer governs access requests triggered when users sign in or machines request resources. It determines whether access is granted, denied, or requires additional verification.

Fixed access policies

Role: Grant access based on predefined rules

Fixed policies allow access based on static authentication requirements, regardless of context, such as device posture or location. While simple, they provide limited adaptability to risk.

Conditional access policies

Role: Adjust access decisions based on context and risk

Conditional access evaluates contextual signals (such as device posture, location, and risk indicators) to dynamically decide whether to allow, block, or challenge access.

4. Internal permissions and privilege control

Once access is granted, this layer defines what an identity is authorised to do within the system. It is comparable to receiving a key card configured for specific areas within a building.

Role-based access control (RBAC)

Role: Assign permissions based on predefined roles

RBAC assigns permissions based on job roles (e.g. accounting, operations) or group membership (e.g. executives, management, analysts), simplifying access management and aligning access with organisational structure.

Attribute-based access control (ABAC)

Role: Refine role-based permissions using attributes and context

ABAC evaluates dynamic attributes (such as project involvement, data sensitivity, or time of access) to enable more granular authorisation decisions.

Privileged access management (PAM)

Role: Secure and monitor high-impact accounts

PAM protects accounts with elevated permissions by isolating credentials, limiting usage windows, and providing visibility into privileged activity. Sessions may be monitored or recorded to ensure sensitive actions are visible, auditable, and attributable to a specific identity.

Just-in-time (JIT) access

Role: Provide temporary elevation when required

JIT grants time-limited privileged access for specific tasks and automatically revokes it, reducing exposure to standing administrative rights.

Least Privilege Access Control

Role: The principle of restricting access to the minimum permissions necessary using appropriate control mechanisms.

Least privilege access control (often called the Principle of Least Privilege, or PoLP) ensures identities are granted only the access required to perform their defined tasks, reducing potential impact if compromised. Organisations implement least privilege through the aforementioned controls such as RBAC, ABAC, and JIT provisioning.

5. Ongoing management, monitoring, and response

The final layer ensures identity security operates continuously rather than as a one-time configuration. It includes:

Identity lifecycle management

Role: Manage identities consistently from creation to decommissioning

Lifecycle management governs how identities are provisioned, updated, reviewed, and decommissioned. It ensures identity data remains accurate over time and that access stays aligned with real-world changes, such as role updates or organisational restructuring.

Joiner-mover-leaver (JML) processes define how access is provisioned when a user joins, adjusted when their role or responsibilities change, and removed when they leave.

Identity threat detection and monitoring

Role: Detect and surface suspicious identity-related activity

Identity monitoring focuses on identifying abnormal behaviour such as unusual sign-in patterns, risky access attempts, or unexpected privilege use. These signals (altered through the central IAM) help security teams detect compromised accounts and respond before damage occurs.

Incident response for identity-related breaches

Role: Contain and recover from identity compromise

Identity-focused incident response (defined in IAM) outlines how organisations respond when an account, credential, or identity system is compromised. This includes disabling accounts, revoking access, rotating credentials, and validating that access is restored securely.

Access reviews and governance controls

Role: Ensure access remains appropriate, auditable, and compliant

Access reviews and governance controls provide structured ways to regularly validate who has access to what and why. They support compliance requirements, reduce long-term risk, and help organisations demonstrate accountability over identity-related decisions.

How identity security supports zero trust

Zero trust is a pivot away from traditional network security. Instead of trusting all identities (human and non-human) within a network, zero trust requires identities to be verified regularly, regardless of location, humanity, or IP address.

In other words:

- Traditional perimeter security: Trust is established at the entrance to a network, application, or environment. Identities are only verified once.

- Zero trust: Trust is regularly challenged, regardless of context. This requires regular verification of users, devices, APIs, scripts, sessions, etc.

These regular identity checks make identity security the key technical requirement for zero trust. Without it, the entire security model fails. Here are the specific parts of the identity security stack mapped onto key zero trust concepts:

Explicit identity verification

Zero trust requires that every access request be verified rather than trusted by default. Identity credentials, such as passwords, passkeys, MFA, certificates, and tokens, are used to continuously verify the identity of users, applications, and APIs.

Continuous access evaluation

Zero Trust relies on ongoing access checks. Conditional access policies reassess context such as device state, location, and risk signals to determine whether access (first-time or existing) should be allowed, blocked, or challenged again.

Granular permission controls

Zero trust assumes that any identity could be compromised at all times. Permission models such as RBAC, ABAC, and least-privilege enforcement limit what users and systems can access once inside the network or environment, reducing the potential impact of a breach.

Risk-adjusted checks to optimise zero trust

The regular checks required for zero trust can strain the user experience, API usability and network performance. Risk-adjusted identity security ensures that resources focus on higher-risk scenarios. Controls such as privileged access management (PAM) and just-in-time (JIT) access ensure sensitive access is tightly scoped, time-limited, and monitored.

Check both human and non-human identities

Zero trust applies to human users, as well as non-human applications, services, and APIs. Machine authentication mechanisms such as certificates, tokens, and mutual TLS ensure system-to-system access is verified and restricted in the same way as human access.

Continuously monitoring identity

Zero trust operates on the assumption that compromise is possible, so it is possible to go beyond identity checks at fixed intervals or specific triggers. Identity threat detection, 24/7 monitoring, and incident response processes enable rapid detection of suspicious behaviour and swift containment when regular identity controls fail.

Maintaining trust over time

Zero trust requires both identity micromanagement and long-term consistency. The aforementioned components focus on day-to-day zero trust. Still, others such as the Joiner–Mover–Leaver (JML) process, identity lifecycle management, and access reviews, ensure that identities and permissions remain accurate as users, roles, and systems change.

The risks of poor identity security for businesses

Identity compromise creates regulatory, financial, operational, and reputational risk across the organisation. The consequences are rarely limited to IT.

Here are the main risks to be aware of:

- Regulatory non-compliance: Weak control over access to regulated data may result in fines, enforcement action, failed audits, or mandatory remediation programmes — even where no confirmed breach has occurred.

- Legal liability: Inability to demonstrate appropriate identity safeguards can increase exposure to contractual disputes, negligence claims, or data protection litigation following an incident.

- Financial loss: Compromised identities allow attackers to operate as legitimate users within systems, potentially leading to fraud, unauthorised transactions, incident response costs, legal fees, and business interruption losses.

- Operational disruption: Identity compromise or containment actions can restrict access to critical systems, causing employee lockouts, service outages, and workflow delays.

- Reputational damage: Identity breaches often directly affect customer accounts or sensitive data, eroding trust, increasing churn, and damaging long-term brand value.

- Loss of intellectual property: Weak access controls can expose trade secrets, strategic plans, or proprietary information, potentially undermining competitive advantage.

- Third-party and supply chain risk: Compromised identities may be used to access connected partner or customer systems, increasing downstream ecosystem risk.

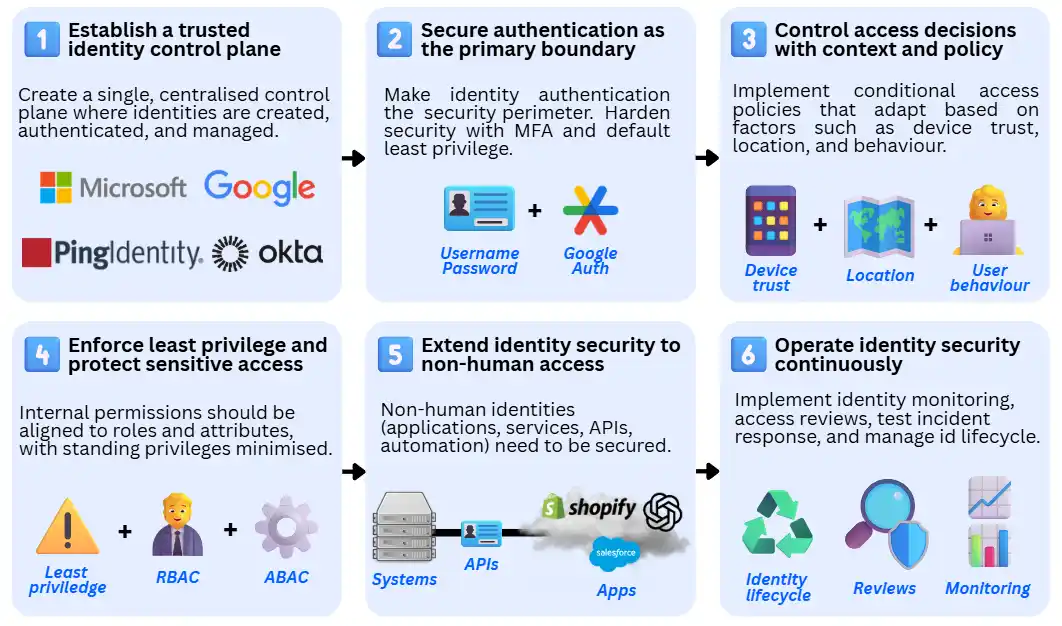

Building an effective identity security strategy

Like all branches of cybersecurity, the appropriate identity security model depends on the organisation’s size, complexity, threat exposure, and the sensitivity of its systems and data.

A small organisation protecting non-critical systems does not require the same depth of controls as a government department or critical national infrastructure operator.

However, regardless of scale, effective identity security follows a consistent progression.

1. Establish a trusted identity control plane

The priority is ensuring there is a single, authoritative place where identities are created, authenticated, and managed. This includes consolidating identity providers, directories, and authentication flows to ensure consistent, centrally enforced access decisions.

At this stage, the focus is not on sophistication, but control and visibility: knowing which identities exist, where they authenticate, and which systems rely on them.

2. Secure authentication as the primary security boundary

Once identity is centralised, organisations should harden authentication to reflect its role as the main perimeter (especially for businesses transitioning from older security models). This typically involves enforcing strong multi-factor authentication for all users and removing legacy or weak authentication methods (e.g. SMS).

Administrative and high-risk access should be prioritised first, followed by broader workforce and external access. The goal is to ensure that stolen credentials alone are insufficient to gain meaningful access.

3. Control access decisions with context and policy

With authentication secured, organisations can move beyond static access rules and begin evaluating context and risk at sign-in and during sessions. Conditional access policies allow access requirements to adapt based on factors such as device trust, location, and behaviour.

This stage marks the transition from basic identity security to identity-driven risk management and is a key enabler of zero trust architectures.

4. Enforce least privilege and protect high-impact access

After access decisions are reliable, attention should shift to what identities can do once access is granted. Permissions should be aligned to roles and attributes, with standing privileges minimised.

Privileged access should be isolated, time-bound, and closely monitored. This limits blast radius and reduces the impact of inevitable credential compromise.

5. Extend identity security to non-human access

As organisations mature, non-human identities (applications, services, APIs, automation) often outnumber human users. These identities must be brought under the same governance model as people: strong authentication, scoped permissions, and lifecycle management.

This step is critical for cloud-native environments, API ecosystems, and supply-chain integrations.

6. Operate identity security continuously

The final stage is ensuring the identity security operation remains ongoing, and not a one-time implementation. This includes continuous monitoring for identity threats, regular access reviews, tested incident response procedures, and lifecycle governance to keep permissions accurate over time.

At this point, identity security becomes self-reinforcing: controls generate signals, signals drive response, and governance ensures long-term correctness.

Organisations without the internal capabilities to do so should look for a managed security partner.

Identity security for businesses – FAQs

Our business broadband experts answer frequently asked questions regarding identity security:

Is identity security the same as IAM?

No. Identity security is the broader discipline of controlling and protecting access to systems and data, while Identity and Access Management (IAM) is the platform used to enforce those controls. IAM is the mechanism; identity security is the strategy.

Why is MFA so important?

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) is the single most effective control against credential-based attacks. Even if a password is stolen, reused, or phished, MFA blocks unauthorised access.

Is identity security only relevant for cloud-based businesses?

No. Identity security applies to any environment where users or systems authenticate, including VPNs, locally-hosted SD-WAN solutions, business VoIP phone systems, intranets, local drives, and on-premises systems.

Can identity security prevent ransomware attacks?

It cannot stop all ransomware, but it significantly reduces risk and impact. Strong authentication, least-privilege access, and privileged access controls limit lateral movement and large-scale deployment. Identity security works alongside endpoint detection and response (EDR), business data backup, and network protection.

What happens if identity systems are compromised?

A compromised identity system can grant attackers wide access across applications and environments. Response typically includes disabling accounts, revoking sessions and tokens, rotating credentials, and validating configurations before restoring access.

How quickly can identity security controls be implemented?

Basic controls such as centralised authentication, MFA and RBAC can often be deployed within days or weeks. Advanced controls, such as privileged access management or formal governance, usually require a phased implementation over several months.

Does identity security replace antivirus or endpoint protection?

No. Identity security prevents unauthorised access and limits privileges, while endpoint protection and business antivirus detect and respond to malware that may have filtered through to devices, servers, or other endpoints. The three are essential components of a layered security strategy.