A guide to Single Sign On (SSO) for businesses

Single Sign-On (SSO) lets users access multiple business apps and systems through a single set of credentials, eliminating the need to remember and enter multiple usernames and passwords at every login.

It enables IT teams to centrally manage and monitor access across all systems, defining access rules, revoking permissions for departing employees, and tracking suspicious logins.

This guide explains how Single Sign-On works, the main types of SSO used across systems, and how to implement it effectively.

Contents

- What is Single Sign-On (SSO)?

- How does Single Sign-On work?

- Types of Single Sign-On (SSO)

- How SSO is implemented in business environments

What is Single Sign-On (SSO)?

Single Sign-On is a login method that allows users to access multiple apps or systems using a single set of credentials. Once they sign in through a central Identity Provider (IdP), they can seamlessly transition between connected services without needing to log in again.

A common example is when a user signs in to their company’s Microsoft 365 account (the Identity Provider) with one set of credentials (username, password, one-time code) and instantly gains access to all linked Microsoft (Exchange, OneDrive, Teams) and third-party (LinkedIn, Salesforce) platforms.

In contrast, older sign-in models required separate credentials for each application. This often led to weak or reused passwords, inconsistent security practices, and additional administrative overhead for IT teams.

Aside from user access, SSO can also facilitate secure communication between apps. The IdP acts as a trust broker, allowing systems to ‘login’ with each other, so all requests (for example, during API calls) can proceed without requiring repeated authentication.

SSO is not a stand-alone system; it’s a feature within the broader Identity and Access Management (IAM) framework. While it simplifies and centralises logins, SSO works alongside other IAM components, such as Identity Provider (IdP), Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), and Conditional Access, to deliver a complete cybersecurity solution.

How does Single Sign-On work?

Single Sign-On always operates on the same core principles:

- Centralised authentication: Users/apps authenticate once with an Identity Provider (IdP), which then automatically authenticates them to all supported platforms.

- Uses tokens and certificates, not passwords: The IdP doesn’t store passwords for each platform. Instead, it exchanges secure digital tokens that prove identity and permissions.

- Centralised management: IT teams manage access and permissions to all platforms centrally through the IdP, enforcing policies, MFA, and monitoring from one place.

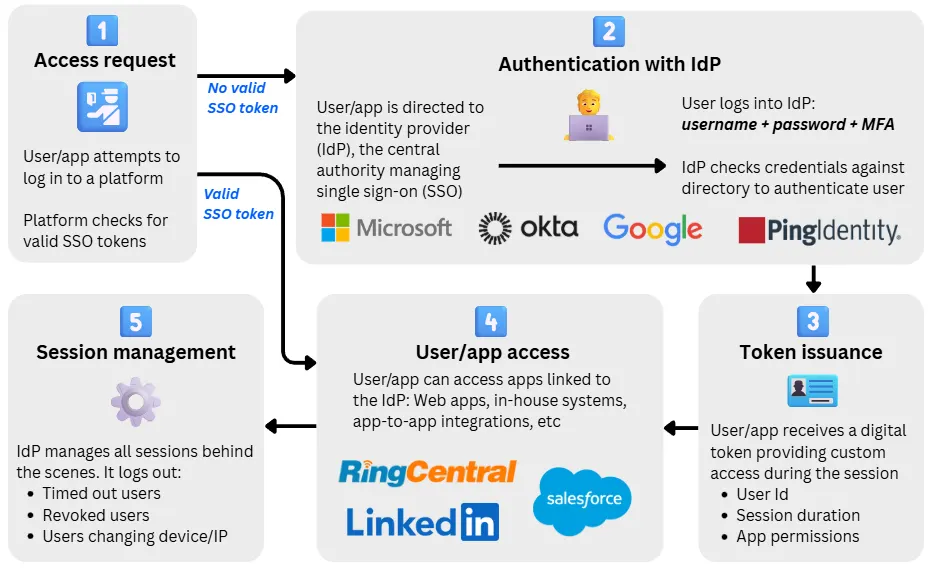

The diagram below shows a typical SSO authentication flow and how these principles work in practice:

1. User or system requests access to a business platform

When a user or system attempts to open a business platform (e.g. an SD-WAN provider portal, a company intranet, or an automated system connection), the application first checks whether a valid SSO session already exists.

The app looks for a trusted token or another authentication proof showing that the user or system has already been verified by the organisation’s identity provider (IdP).

- If a valid session exists: Access is granted immediately with the appropriate permissions.

- If a valid session does not exist: The app automatically redirects the request to the IdP for authentication.

This redirection or trust exchange occurs automatically and invisibly, using secure protocols such as SAML, OAuth 2.0, or OIDC, depending on the SSO method in use.

2. Authentication with the Identity Provider (IdP)

When the access request reaches the organisation’s identity provider (IdP), the user or system must authenticate to prove their identity.

- For human users: This usually involves entering a username, password, and completing a phishing-resistant MFA step.

- For systems or automated connections: Presenting a digital key or certificate that proves their identity to the IdP.

Once authenticated, the IdP becomes responsible for verifying the user or system across all connected platforms according to the SSO access policies configured by the IT team.

What is the IdP in the context of SSO?

The IdP is the central authority for identity and access within an organisation. It stores user records, authentication methods, and permissions across all connected business platforms.

It acts as the brain for identity and access management, verifying who the user or system is, applying security policies (such as password rules, MFA, and conditional access), and issuing secure tokens that connected applications trust.

Common business identity providers with SSO capabilities include:

- Microsoft Entra ID: Part of the Microsoft 365 suite, used widely for Web SSO and conditional access.

- Google Identity: Integrated with Google Workspace, managing authentication across Google and third-party apps.

- Okta: Dedicated Identity and Access Management (IAM) platform.

- Microsoft Active Directory: On-premises directory service powering Enterprise SSO for Windows domains.

- Apigee/Kong/AWS API Gateway: Act as IdPs for app-to-app SSO, managing trust between systems through tokens or certificates

Regardless of the platform, the IdP is the single source of truth for identity, maintaining trust and access across all systems and users.

3. Issuing secure tokens for each platform

Once the user or system has passed the IdP login, the IdP issues it with digital tokens: Secure, time-limited proofs of identity. A separate token is issued for each supported app.

These tokens act like digital passes, containing key details such as:

- Identity: User ID, email, department, and role (used to assign access permissions).

- Access permissions: For example, an account manager may only have read-only access to a CRM database.

- Authentication event: The date, time, and IP of the login, used for detecting suspicious activity.

Importantly, tokens never contain passwords and are cryptographically signed so their integrity can be verified by other systems.

SSO token formats

Different types of SSO use different token formats:

- SAML assertions: XML-based documents that securely pass user identity data between a browser and web or SaaS applications.

- JWTs (JSON Web Tokens): Compact, digitally signed tokens used in OpenID Connect (OIDC) setups to share verified user details between apps.

- OAuth 2.0 access tokens: Temporary credentials that allow one app to securely access another’s API or data on behalf of a user or system.

How the SSO tokens work

When a token reaches an application (the service provider), the app validates its digital signature using the IdP’s public key. If the token is valid and unexpired, access is granted automatically.

Tokens expire after a set time to reduce risk. Some systems use refresh tokens to extend sessions securely. Both can be revoked instantly if a session is compromised.

The application then reads the token’s contents to apply the correct permissions, all without another login. This secure exchange of verifiable tokens is what enables SSO to deliver simple, centralised, and trusted access across every system.

4. User is granted access

Once the application validates the token, access is granted automatically. The user or system can now move seamlessly between authorised applications under the permissions defined in the token.

Each connected system recognises the same trusted identity, so verification happens silently in the background. It could be an employee switching between cloud tools, a desktop user accessing internal resources, or one business system sharing data with another.

5. Session management

After access is granted, the Identity Provider (IdP) manages the session behind the scenes. This session represents a trusted state, allowing users or systems to stay signed in without re-entering credentials for every application.

The IdP defines how long the session lasts and can terminate it early if a user logs out, changes devices, or if access is revoked. When that happens, all connected applications lose access immediately.

This central control lets IT teams monitor activity, enforce security policies, and quickly end sessions if suspicious behaviour is detected. It keeps Single Sign-On convenient for users while ensuring the organisation remains in full control.

Types of Single Sign-On (SSO)

SSO always aims for a single login across multiple systems, but its design must adapt to each specific environment. Cloud platforms, internal networks, and app-to-app integrations all handle identity and trust differently, giving rise to several types of SSO.

Below are the main types of SSO solutions and where each fits best:

Web SSO (browser-based)

Web SSO is the most common form of Single Sign-On. It’s used for cloud and SaaS applications such as Salesforce, Slack, or HubSpot, all managed through a single, cloud-based Identity Provider (IdP), typically Microsoft 365 or Google Workspace.

When a user signs in to the IdP, that single login automatically grants access to all other connected browser-based apps.

Note that Web SSO is far more secure and controlled than consumer “Sign in with Google” or “Sign in with Apple” options. In Web SSO, the IdP is managed by the company’s IT team, not by individual users.

They can tailor security policies for each role or department, adding more complex rules for access control depending on the user and platform risk.

Enterprise SSO (desktop, internal apps)

Enterprise SSO is built for office-based systems and internal networks, rather than cloud apps.

Unlike Web SSO, which works through a browser and online services, Enterprise SSO operates inside a company’s own local area network, covering things like desktop logins, shared drives, and internal software.

It relies on technologies such as Microsoft Active Directory and Kerberos. When an employee signs in to their computer, that single login automatically unlocks everything they’re permitted to access, from file servers to databases, without needing to log in again.

This setup is particularly valuable for organisations running legacy or custom-built applications that don’t support modern web authentication standards.

App-to-app SSO (server-to-server trust)

App-to-App SSO (also known as service-level authentication) enables applications to authenticate directly with one another, without human involvement.

Each system uses API tokens, certificates, or OAuth credentials to verify that the other is trusted and authorised to exchange data.

It’s common in cloud integrations, such as a business VoIP phone system logging call data into a CRM, or a CRM pulling analytics from another service automatically.

The trust relationship is handled entirely behind the scenes through secure token exchanges, ensuring smooth and secure automation between systems.

Federated identity (cross-domain SSO)

Federated SSO extends single sign-on beyond a single organisation’s boundary. It allows users from one company or domain to access another organisation’s systems without creating a separate login.

This works through a trust agreement between two identity systems, for example, a company using Microsoft Entra ID (Azure AD) and a partner using Google Workspace. Each organisation maintains control over its own users but agrees to recognise the other’s verified identities.

In practice, an employee can use their existing company credentials to access a partner portal or shared platform. It’s instrumental in supply chains, partnerships, joint ventures, or during mergers and acquisitions, where secure collaboration between organisations is required.

Because trust extends across systems, a compromise in one organisation could affect another (for example, the 2025 supply chain cyberattacks). For this reason, federated setups demand careful management of security policies, access levels, and trust relationships to maintain integrity.

Social login (SSO via external identity providers)

Social login lets users access business or web applications using their existing accounts from popular platforms, such as:

- “Sign in with Google”

- “Sign in with Microsoft”

- “Sign in with Apple.”

Instead of creating a new username and password, users authenticate through their external provider. This is convenient for contractors, partners, or customers who already have those accounts, reducing friction and support overhead.

However, this approach shifts identity control to an external platform. Businesses then rely on the provider’s security policies, uptime, and authentication standards, and have limited visibility into password rules or recovery processes, making it best suited for small teams.

How SSO is implemented in business environments

Deploying Single Sign-On means establishing a trusted connection between an organisation’s Identity Provider (IdP) and the applications employees use every day.

While the technical setup varies between small businesses and large enterprises, the implementation process generally follows the same key stages, from choosing the IdP to managing users and monitoring access.

1. Choose and connect to an Identity Provider (IdP)

Every SSO deployment begins with selecting and configuring an Identity Provider (IdP), the system that stores user identities, roles, and permissions, and issues trusted login tokens.

- A cloud-first company such as a marketing agency might already use Google Workspace, Microsoft Entra ID, or Okta as its IdP, which can act as the foundation for SSO immediately.

- A large retailer like a department store, with on-premises infrastructure might use Active Directory internally and connect it to a cloud IdP such as Entra ID or Ping Identity to extend single sign-on across both local and cloud environments.

The IdP becomes the single source of truth for all users before SSO can be rolled out further.

2. Establishing trust and integrating apps

Once the IdP is in place, each application must be connected so it can trust the tokens the IdP issues.

- A retail business, for example, might integrate cloud apps like Shopify, Xero, and Slack easily through simple admin dashboards.

- A logistics company with older internal systems might need to use connectors or middleware to link legacy software to the IdP.

In either case, the goal is to create a trusted network of applications that all recognise the same central identity system.

3. Configuring authentication flows

Authentication flows define how users log in, what checks are applied, and how risk is managed.

- A remote-first digital agency might use passwordless authentication or biometric logins for convenience.

- An engineering firm with on-site servers might implement MFA for remote access, or conditional access policies that only allow logins from company-owned laptops.

The principle remains the same: authenticate once, then extend that trust securely across every authorised system.

4. User onboarding and rollout

When SSO is ready, it’s rolled out to users, either all at once or in stages.

- A startup might switch all staff in a single day, replacing multiple logins with one company-wide portal.

- A big organisation might pilot SSO in one department first, ensuring everyone’s apps connect properly before scaling up.

Clear communication and user training are essential. Staff should understand what’s changing (“one login for everything”) and how to recover access through MFA or backup options.

5. Ongoing management and monitoring

After launch, SSO becomes part of the organisation’s regular identity management practice.

- A financial services company might integrate SSO logs into its cybersecurity compliance monitoring tools, ensuring every login is tracked.

- A creative agency might simply rely on the built-in reports from its IdP to review access and remove inactive accounts.

Over time, IT teams add new apps, adjust permissions, and review user activity, all from one central dashboard instead of managing separate logins for every system.

Is SSO secure?

When properly implemented, Single Sign-On is one of the most secure ways to manage user access and transition into zero trust.

By centralising authentication, SSO allows IT teams to enforce strong, consistent security policies across all business systems, while giving users a simpler way to sign in.

However, because SSO concentrates authentication in one place, it also becomes a single point of failure that can be exploited effectively if not properly designed and maintained.

How does SSO improve security?

There are four key reasons why SSO makes systems more secure:

- Fewer credentials to manage: Employees only need one set of credentials, reducing the temptation to reuse weak passwords or store them insecurely. With fewer passwords in circulation, there’s less for attackers to exploit.

- Centralised control: IT teams can apply and enforce uniform security policies (password complexity, MFA, device checks) across every connected application. This ensures consistent protection no matter which tool users access.

- Rapid response to threats: If any account is compromised or a staff member leaves, administrators can revoke access to all apps at once through the IdP. This automatically cuts off every connected system, preventing lingering logins or forgotten accounts from becoming attack points.

- Unified visibility and auditing: All login activity flows through the same identity system, giving businesses a single, detailed audit trail. Suspicious behaviour or failed MFA attempts can be identified quickly, and dark web monitoring or breach alerts cover all connected accounts at once.

What security risks does SSO bring?

There are four key risks that SSO brings, whose effects can be mitigated with an appropriate deployment:

- Single point of failure: If the SSO platform itself is breached or goes offline, all connected applications are affected. Mitigation includes enforcing MFA, using redundant IdPs, and ensuring disaster recovery processes exist for critical apps.

- Over-trusted integrations: Poorly configured app-to-app SSO might accept tokens from unauthorised sources. Businesses should always verify token validation rules and signatures are correctly implemented to prevent token forgery or misuse.

- Session hijacking and token theft: Because SSO relies on tokens, attackers may try to steal them from a user’s browser or device. Encryption, short token lifetimes, secure cookie handling, and the use of refresh tokens with revocation controls help minimise this risk.

- Insider access abuse: Centralised identity systems become high-value targets for insider threats. Applying role-based access controls (RBAC) and least-privilege principles limits exposure, ensuring users only have access to the systems and data necessary for their role.

Why is SSO essential for businesses?

SSO isn’t an optional upgrade anymore, but a standard part of secure, modern IT management. Like multi-factor authentication, SSO has become a baseline expectation for controlling access safely and efficiently.

For SMEs, it’s straightforward to implement and integrates with the common business tools companies already use. It comes with Microsoft 365, Google Workspace, or Okta, meaning the cost barrier is minimal compared to the security and efficiency it delivers.

Here is a complete list of all the benefits that make it an essential access management tool:

- Centralised user management and provisioning: Control all user access from a single location. Add, update, or remove permissions instantly across every connected system.

- Reduced login friction: Employees sign in once to access everything they need (email, CRM, VoIP), reducing wasted time.

- Stronger access control and compliance: Consistent enforcement of MFA, policies, and audit trails helps meet standards like ISO 27001, GDPR, and Cyber Essentials.

- Reduced IT workload: Fewer password resets and manual account changes mean smaller helpdesk queues and more focus on strategic IT priorities.

- Built-in integration with existing platforms: Most major business tools already support SSO, enabling fast and cost-effective deployment.

- IAM (Identity and Access Management): SSO is a core component of an integrated IAM cybersecurity solution, enabling Zero Trust and secure cloud expansion.