What is DDNS (Dynamic DNS)? Self-hosting without a static IP

When getting a static IP address is impossible, Dynamic DNS (DDNS) remains the best practical alternative to hosting business services like VPNs, file storage, or apps.

This guide explains what DDNS is, how it works, when businesses should use it, and how to set it up securely.

Contents:

What is Dynamic DNS (DDNS)?

Dynamic DNS (DDNS) is a service used by businesses to host digital services (e.g. VPNs, websites, VoIP, local files) on premises using the default dynamic IP address (an address that changes periodically) given by their business internet provider.

DDNS is used when static IPs (the preferred hosting service) are unusable, unavailable or unviable. For example, when the hosting site is connected via mobile/satellite broadband, or in rural areas where providers don’t always offer static IP.

It works by automatically updating the internet’s DNS records whenever the internet provider rotates IP addresses. This ensures the domain name always points to the correct location, without requiring manual updates.

Without DDNS, any hosted services would become unreachable as soon as the IP address changes, since users would still be directed to the old, invalid address.

When is DDNS necessary for hosting?

Static IPs are the standard business choice for hosting because they are stable, reliable, and affordable. Most business broadband packages include them, or add them for a small monthly fee (typically £5–15).

However, there are situations where static IPs are not available, not practical, or simply not worth the cost. In these cases, DDNS provides a workable alternative:

- CGNAT environments: Mobile (4G/5G) and satellite broadband services sit behind carrier-grade NAT (CGNAT) where static IPs aren’t possible. DDNS is the only option in these scenarios, including when such connections are used as backup links.

- Limited static IP availability: Some business broadband providers, rural networks, or lower-tier business plans don’t offer static IPs, forcing businesses to rely on DDNS.

- Multi-site or micro deployments: Organisations with many small sites, IoT gateways, or kiosks with outbound services (e.g. CCTV, smart locks) avoid the cost of multiple static IPs by using DDNS.

- Consumer broadband for business use: Microbusinesses or startups running on residential lines without static IPs turn to DDNS for hosting.

- Legacy setups: Older infrastructures that were built initially with DDNS may remain in place, even though static IPs are now cheaper and more accessible.

- Ultra-low-margin or free hosting: Some services use DDNS to eliminate even small static IP costs, keeping overheads at a minimum.

How DDNS works

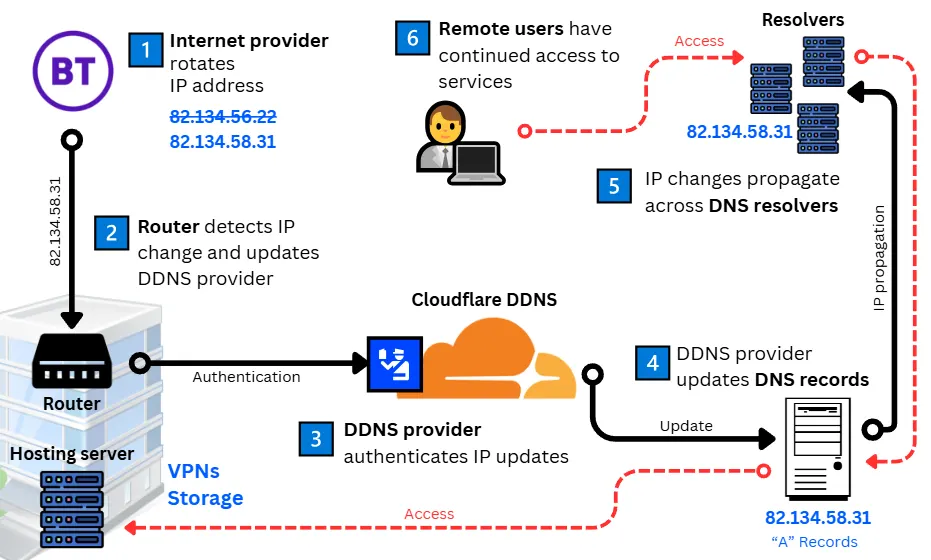

Dynamic DNS (DDNS) keeps self-hosted services accessible, even when a business broadband provider reassigns its IP address. It does this by detecting IP address changes and automatically updating DNS records, ensuring the domain name always points to the correct location.

Here’s how the process typically works:

1. Broadband providers periodically rotate IPv4 and IPv6 addresses

Business broadband connections often use dynamic IPv4 addresses, which are regularly reassigned to manage limited address space. Some providers also rotate IPv6 prefixes, though less frequently. Each change breaks inbound connections unless DNS records are updated.

2. Router or client detects changes and sends updates

When an IP change occurs, the business broadband router (or a DDNS client running on a server) automatically detects it and prepares an update request. This request is sent securely to the DDNS provider over HTTPS, following the provider’s API format.

3. DDNS provider verifies requests before making changes

To prevent tampering, the DDNS provider verifies the request using stored credentials, API keys, or tokens. Only authorised devices can make updates.

Alternatively, many businesses run their own DDNS client in-house, which avoids third-party costs but requires more management. See the differences here.

4. Updated IP addresses are mapped to DNS records

Once verified, the DDNS provider updates the relevant DNS records with the new IP:

- “A” record: Maps a domain name to an IPv4 address

- “AAAA” record: Maps a domain name to an IPv6 address

Supporting both ensures compatibility with dual-stack broadband providers and reduces reliance on NAT (Network Address Translation), which is commonly required for IPv4.

5. DNS changes propagate quickly across the internet

The provider’s authoritative servers publish the update, and recursive DNS resolvers (i.e., servers containing large lists of domain names and IP addresses) around the world refresh their records. Thanks to low TTL (time-to-live) values, this usually happens within 30 seconds to 5 minutes.

6. Services remain accessible under the same domain name

End-users continue to access services through the same domain name, unaware of the change. Behind the scenes, DDNS ensures that websites, VPNs, or business VoIP phone systems stay online despite dynamic IP reassignment.

Self-hosted DDNS vs third-party Dynamic DNS services

There are two alternatives to manage a Dynamic DNS system. Your business can either:

- Self-host DDNS by setting up DDNS at the router or a local client (server, NAS) to update records directly at the domain registrar or DNS host (if they support API updates), or

- Managed DDNS service such as No-IP, Dyn, or Cloudflare, which provides ready-made infrastructure and dashboards.

Both approaches keep DNS records in sync with changing IP addresses, but they differ in cost, complexity, and management.

| Feature | Self-hosted DDNS | Managed DDNS service |

|---|---|---|

| Setup | Configure a router or run a local client that updates DNS directly at the registrar | Sign up with a third-party provider and link the domain |

| Ease of use | Moderate: requires a domain registrar with API support and some technical setup | Easy: web dashboards, apps, and built-in router support |

| Reliability | Depends on local router or client uptime | Provider’s reliability with redundant infrastructure |

| Cost | Free if registrar supports API updates, some may require a paid DNS add-on | Free tiers exist, paid plans typically low (£5–£15/month) |

| Security | Keys and credentials managed locally | Providers handle secure updates, authentication, and monitoring |

| Flexibility | Full control over DNS records | May be limited to provider’s platform and features |

Security best practices for DDNS

Dynamic DNS (DDNS) ensures services remain accessible, but it also makes internal systems visible on the public internet. This increases the attack surface, so businesses must apply strong security measures to keep those services safe.

At a minimum, any business using DDNS should:

- Avoid exposing raw services directly

- Enforce strong authentication

- Keep basic logs and monitor activity

Here is how to do this in practice:

1. Use a VPN or reverse proxy/tunnel to shield raw services

Directly exposing services like remote desktop logins, file shares, or databases through DDNS is highly risky and often targeted by attackers.

Instead, provide secure remote access using a VPN, reverse proxy, secure tunnel, or a business SD-WAN solution with integrated security features. This principle applies whether it’s a small office exposing CCTV feeds or an SME hosting file servers.

2. Harden authentication and perimeter controls

Security controls should match the type of service being exposed:

- Firewalls: Limit open ports strictly to what is required (e.g. if hosting a VPN, only the VPN port should be accessible).

- Web Application Firewalls (WAFs): For web-based services, a WAF helps block common attacks such as SQL injection or cross-site scripting.

- Mutual TLS (mTLS) or IP allow-lists: For highly sensitive systems, such as remote management dashboards or finance databases, add stronger restrictions.

- Authentication: Always enforce strong passwords, multi-factor authentication (MFA), tokens, or certificates for every DDNS endpoint.

3. Enable logging, alerting, and rate-limits

Any DDNS-exposed service should be treated as an internet-facing service. Enable logging at the router or DDNS client level, and review logs regularly for unusual activity, such as repeated failed login attempts.

For stronger protection, integrate with network monitoring tools to trigger alerts on suspicious activity. Apply rate-limiting where possible to slow brute-force attempts against VPNs, SSH, or web portals.

Hosting under CGNAT (4G/5G/satellite) using DDNS

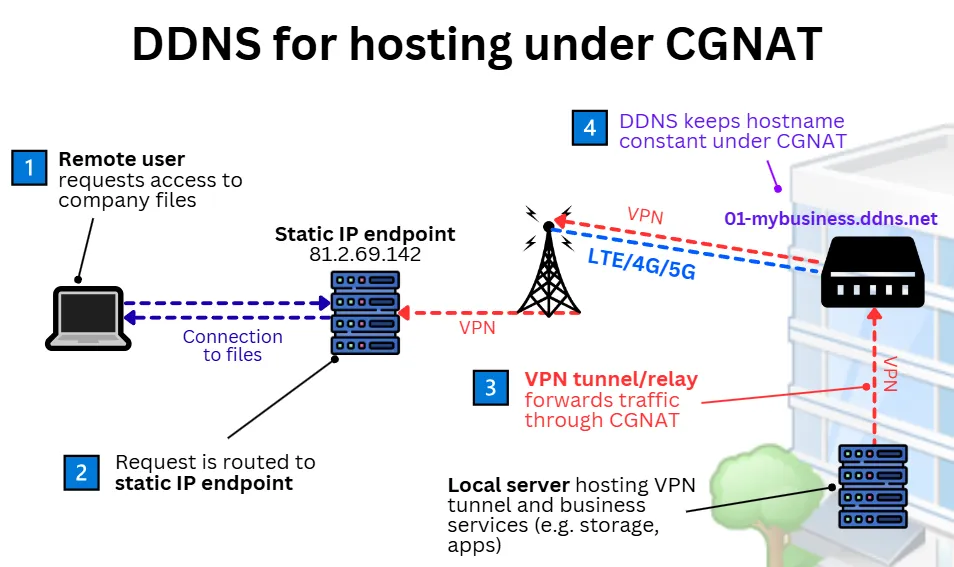

Business mobile broadband and business satellite broadband are widely used in rural locations where fixed lines are unavailable and as backup connections for broadband failover. However, these links usually operate behind Carrier-Grade NAT (CGNAT).

Under CGNAT, thousands of customers share the same public IP address. Instead of assigning each location its own internet-reachable IP, the provider assigns private IPs: internal addresses that function within the carrier’s network but are not visible on the public internet.

This setup renders hosting services impossible without a workaround, as they have no reachable address. Providers can’t extend a valid static IP because the technology doesn’t permit it, and DDNS has no unique dynamic IP to track under CGNAT.

Using DDNS and outbound tunnels/relays

To work around the CGNAT limitation, hosted services are made reachable through an external endpoint. This endpoint, such as a cloud server, another branch site, or a service provider’s gateway, has a static, routable IP address where users connect.

From the CGNAT site, an outbound tunnel is established to the external endpoint. Outbound traffic is always allowed under CGNAT, so the tunnel remains active regardless of how frequently the carrier changes IP addresses.

Here, DDNS plays a critical role:

- It provides a stable hostname for the tunnel, even as the CGNAT site’s private and carrier-assigned addresses change.

- It ensures the external endpoint can always find and maintain the connection back to the site.

- Effectively, services appear to be “hosted” at the external endpoint, while in reality they are relayed back to the CGNAT site through the tunnel.

DDNS business use cases

As a solution for hosting without static IPs, Dynamic DNS (DDNS) is typically used in small-scale or niche business applications. Here are the most common, real-world applications of DDNS:

- VPN access: Remote staff can securely reach office systems (e.g. finance tools, file shares, printers) even if connectivity fails over to a mobile or satellite link.

- CCTV and security monitoring: Retail or office camera feeds, alarms, and access controls remain viewable remotely when connections switch or load-balance.

- Self-hosted VoIP: On-premise phone systems, UCaaS, and other self-hosted VoIP integrations stay reachable when IPs change, avoiding dropped calls during failover.

- Development and test environments: Developers and testers can expose locally hosted apps, demos, or staging environments through a stable hostname without needing static IPs.

- IoT and remote monitoring: Smart building systems, sensors, and smart meters at branch sites can be accessed over dynamic or mobile broadband.

- Specialist remote operations: In industries such as energy, agriculture, transportation, or manufacturing, DDNS supports access to systems running on mobile or satellite links, including pipeline monitoring, offshore communications, soil monitoring, and telemetry tools.

💡 Not heard of VoIP? Read our What is VoIP? guide.

Setting up business DDNS

Businesses that choose to self-host DDNS have two main options: configuring it directly on the broadband router or running an update client on a local device such as a server or NAS.

💡 Avoid the setup? With a managed DDNS service such as No-IP, Dyn, or Cloudflare, no local configuration is required. A hostname is registered or a domain is connected, and the provider manages updates automatically. See a comparison with self-hosting here.

Router-native DDNS

Most modern business routers support DDNS natively. This is the simplest and most reliable setup, as the router directly updates your DNS provider whenever the public IP changes.

Steps:

- Confirm your router supports DDNS (check the spec sheet or management interface).

- Subscribe to a DDNS service such as No-IP, DynDNS, or Cloudflare DDNS.

- Register a hostname (e.g. yourbusiness.ddns.net).

- Log in to your router admin page (often 192.168.1.1).

- Enter your DDNS account details (username/password or, more commonly now, an API token).

- Save the settings; the router will automatically push IP updates.

Note: Business mobile broadband (4G/5G) and satellite routers are typically configured behind CGNAT, requiring a more complex setup.

Client-based DDNS

If your router doesn’t support DDNS, you can run a small update client on a server, NAS (Network Attached Storage), or host inside your network.

Options include:

- DDNS client software from providers (e.g. No-IP DUC, DynDNS Updater).

- NAS appliances (Synology/QNAP have built-in DDNS clients).

- Custom scripts on Linux/Windows hosts using the provider’s API.

Implementation tips:

- Use a cron job (Linux) or Task Scheduler (Windows) to run the update script every few minutes.

- Keep the TTL (time-to-live) for your DDNS hostname low (e.g. 60 seconds) so DNS records update quickly after an IP change.

DDNS testing and propagation

Once configured, always test that DDNS is working correctly:

- Check your current public IP: Via “What is my IP” in Google or by doing a business broadband speed test.

- Verify DNS resolution:

- Use ping “yourbusiness.ddns.net” and confirm it resolves to your current public IP.

- Use dig “yourbusiness.ddns.net” or “nslookup yourbusiness.ddns.net” to check DNS propagation.

- Simulate an IP change: Restart your router or force a reconnect.

- Check update speed: Ensure your DDNS provider updates within the expected timeframe (usually a few minutes).

- Validate caches: Remember, DNS propagation may be delayed by intermediate resolvers, but with a low TTL, this should be minimal.

Troubleshooting DDNS

Here are some tips on how to troubleshoot DDNS, whether you’re setting up DDNS for your home office or trying to understand how your Managed Service Provider (MSP) is resolving an issue.

Common DDNS issues

If your self-hosted services are inaccessible or pinging your DDNS hostname returns an outdated IP address, consider these possible causes:

- Router misconfiguration: After a router reset (manual or ISP-triggered), your DDNS settings may no longer update. Re-enter your credentials in the router, verify the DDNS service is enabled, and restart.

- Incorrect credentials: Providers sometimes require password resets or updated API keys. Double-check the login details stored in your router or device.

- DDNS provider outages: If the provider is down, your hostname won’t resolve. Confirm on their status page or temporarily switch providers.

- DNS cache delays: Old IPs may linger in local or ISP caches. Flush your local DNS cache or use a global checker like “whatsmydns.net“.

- Conflicting DDNS clients: Multiple devices (router, NAS, etc.) updating the same hostname can create mismatches. Let only one device (ideally the router) handle updates.

- Firewall restrictions: A new or updated firewall may be blocking traffic. Confirm port forwarding is set up correctly and review logs for blocked requests.

- Provider port blocking: Some ISPs block common ports like 80 (HTTP), 443 (HTTPS), or 3389 (RDP). Try using an alternative port (e.g., 8080 instead of 80) or ask your provider to lift the restrictions.

- IPv6 (AAAA) pitfalls: If your provider publishes both IPv4 and IPv6 records, but your IPv6 isn’t configured correctly, remote access may fail. Turn off the AAAA record if you’re not using IPv6.

When to seek a Managed Service Provider (MSP)

If these checks don’t resolve the issue, or troubleshooting keeps eating into your time, an MSP can step in to:

- Manage a static IP endpoint on behalf of your business if under CGNAT.

- Resolve DDNS configuration issues and maintain reliable access to your services.

- Manage firewalls, port forwarding, and security settings.

- Ensure cybersecurity compliance with security frameworks.

- Provide continuous monitoring to avoid revisiting the same DDNS headaches.

Many MSPs package DDNS support into broader services such as:

- Business SD-WAN solutions

- Leased line business broadband (for high-performance applications).

- Cyber Essentials certification.

- Starlink or wireless leased line integration for rural broadband.

💡 MSP is not Managed DDNS: An MSP is not the same as the managed DDNS providers we cover herein. An MSP is a full IT service partner who can implement DDNS, whether by self-hosting it or through a DDNS provider, as part of a wider support package.

FAQs – Dynamic DNS

Our business broadband experts answer some of the most frequently asked questions about DDNS for businesses.

How often does my broadband provider update my public IP address?

It depends on the provider. Some rotate IP addresses every few hours or days, while others assign “sticky” IP addresses that remain stable for months at a time.

Is DDNS different to DNS?

No. DNS (Domain Name System) is the global directory that translates domain names (e.g. www.example.com) into IP addresses.

DDNS (Dynamic DNS) is a specialised service that updates DNS records automatically when a host’s IP address changes. This keeps self-hosted services, such as websites, email, VPNs, or modern AI tools, reachable without manual updates.